If you write fiction, you are making use of an archetype, whether you know it or not. In literature, the word archetype describes the kinds of characters and plots featured in stories across all cultures and eras of human history.

Even in our ancient past, when we had little communication with other cultures, our myths and legends shared common, recognizable characters we call archetypes.

Even in our ancient past, when we had little communication with other cultures, our myths and legends shared common, recognizable characters we call archetypes.

The Writer’s Journey, Mythic Structure for Writers, by Christopher Vogler, details the various traditional types of characters that are featured in mythology and our modern literary canon. His work is based on Joseph Campbell‘s book, The Hero With a Thousand Faces,

The following is Christopher Vogler’s list of character types [1] who are the heroes and villains in every story:

The following is Christopher Vogler’s list of character types [1] who are the heroes and villains in every story:

- Hero: someone who is willing to sacrifice his own needs on behalf of others.

- Mentor: all the characters who teach and protect heroes and give them gifts.

- Threshold Guardian: a menacing face to the hero, but if understood, they can be overcome.

- Herald: a force that brings a new challenge to the hero.

- Shapeshifter: characters who constantly change from the hero’s point of view.

- Shadow: a character who represents the energy of the dark side.

- Ally: someone who travels with the hero through the journey, serving a variety of functions.

- Trickster: embodies the energies of mischief and desire for change.

So, there we have the characters. Now we need a story. Christopher Booker, author of The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories [2], tells us that the following basic archetypes underpin the plots of all stories:

-

Overcoming the Monster

-

Rags to Riches

-

The Quest

-

Voyage and Return

-

Comedy

-

Tragedy

-

Rebirth

-

I would add an eighth: Romance

We feel comfortable with these basic recognizable storylines, no matter how differently they are presented to us. No matter the story, if it is fiction, we have characters in familiar roles, acting out familiar plots.

Yet, despite the basic similarity of these characters and plots and their ancient origins, they are the basis of our modern literary canon. Every author has a story to tell, and it is their imagination, style, and voice that make it new and unique.

Let’s consider two famous novels. First, we’ll look at The Maltese Falcon, by Dashiell Hammett.

Let’s consider two famous novels. First, we’ll look at The Maltese Falcon, by Dashiell Hammett.

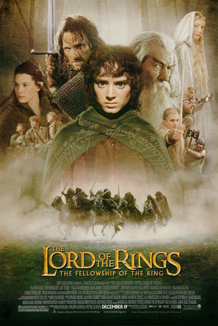

This is a detective novel, a thriller, nothing at all like our other novel, J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit, which is an epic fantasy quest tale.

However different it looks on the surface, The Maltese Falcon is definitely a quest tale.

The genre of this tale is classic thriller with a film noir flavor. Yes, it’s a quest featuring a hero and a villain, but delivered with a twist.

Sam Spade is a hardboiled, cynical private eye. He is hired to retrieve a jeweled statue, the Maltese Falcon. However, the statue itself is a MacGuffin. The MacGuffin’s importance to the plot is not the object or goal itself, but rather the effect it has on the characters and their motivations. In this case, the quest changes Sam’s life. The sole purpose of the MacGuffin is to move the plot forward.

In The Hobbit, home-loving Bilbo Baggins is a comfortable, upper-middle-class hobbit who is tricked into hosting a group of strangers for a dinner. Overcome by a moment of rashness, he joins the wizard Gandalf and the thirteen dwarves of Thorin’s Company. The obvious quest is for Bilbo to break into a dragon’s lair, acting as a burglar to reclaim the dwarves’ home and treasure from the dragon Smaug.

In The Hobbit, home-loving Bilbo Baggins is a comfortable, upper-middle-class hobbit who is tricked into hosting a group of strangers for a dinner. Overcome by a moment of rashness, he joins the wizard Gandalf and the thirteen dwarves of Thorin’s Company. The obvious quest is for Bilbo to break into a dragon’s lair, acting as a burglar to reclaim the dwarves’ home and treasure from the dragon Smaug.

Through the process of fulfilling his burglar tasks, Bilbo finds the Arkenstone, an heirloom jewel prized above all else by the leader of the dwarves, Thorin Oakenshield.

It is a MacGuffin.

In fact, the entire quest, from the moment he leaves home until the day he returns, is a MacGuffin. This is because its sole purpose is to force Bilbo’s personal growth and place him where he will find the One Ring, which will be featured as a core quest in later stories.

In fact, the entire quest, from the moment he leaves home until the day he returns, is a MacGuffin. This is because its sole purpose is to force Bilbo’s personal growth and place him where he will find the One Ring, which will be featured as a core quest in later stories.

By the end of The Maltese Falcon, we learn that the object of the quest was not the purported “Maltese Falcon” after all, despite the lengths they go to acquire it and the efforts the characters expend in the process. The true core of the story is the internal journey of both Sam Spade (the hero) and Brigid O’Shaunessy (the ally/shapeshifter/trickster), two people brought together by the quest, and whose lives are changed by it.

Similarly, the true object of The Hobbit’s quest is not the reclamation of the dwarves’ heritage and treasure. It is how Bilbo Baggins is changed by his experiences and the people he meets on the journey.

So, The Hobbit and The Maltese Falcon begin with the same character archetype of the hero.

- Bilbo (the hero) is hired to steal the Arkenstone for Thorin and the dwarves.

- Sam Spade (the hero) is hired to obtain the Maltese Falcon for Brigid O’Shaunessy.

In both tales, another archetypal role that appears is that of the mentor: Bilbo has Gandalf the Wizard, and Sam Spade has Caspar Gutman. Despite their very different personalities and reasons for offering wisdom, both are mentors. Both offer advice that advances the plot.

Both Brigid O’Shaunessy and Thorin Oakenshield begin as allies but prove to be tricksters, shapeshifting and becoming the shadow.

Both Brigid O’Shaunessy and Thorin Oakenshield begin as allies but prove to be tricksters, shapeshifting and becoming the shadow.

In each tale, the hero endures hardship to acquire an object (the Maltese Falcon or the Arkenstone), only to find that it is no longer as important as he thought. In the process of their journeys, both find joy and sorrow.

Sam Spade never acquires the true Maltese Falcon but finds out who really killed his business partner. He loses much in the process and emerges a different man.

Bilbo Baggins loses his naïveté, and after all the work of finally finding it, he hides the treasured Arkenstone. He does this because of Thorin’s greed and uncharitable actions toward the Wood-elves and the Lake-men who have suffered from the Dragon’s depredations.

And as anyone can tell you, despite their being written in the same era, and the similarities of their archetypal plots and characters, they are radically different novels.

And as anyone can tell you, despite their being written in the same era, and the similarities of their archetypal plots and characters, they are radically different novels.

And that is the beauty of the deeper level of the story.

Something so fundamentally similar as plot archetypes and character archetypes emerges completely unique and (on the surface) wildly dissimilar from others when told by different storytellers.

So, while there may be no “new” stories, your voice, your originality and imaginative twists make the story new and memorable.

Credits and attributions:

IMAGE: The One Ring, Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:One Ring Blender Render.png,” Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:One_Ring_Blender_Render.png&oldid=1051100432 (accessed January 3, 2026).

[1] Wikipedia contributors, “Archetype,”Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia ,https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Archetype&oldid=1321105373 (accessed January 3, 2026).

[2] Christopher Booker (2004). The seven basic plots: why we tell stories. London: Continuum. ISBN 978-0826452092. OCLC 57131450.

Wikipedia contributors, “The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers,”Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia,https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=The_Writer%27s_Journey:_Mythic_Structure_for_Writers&oldid=1324459018 (accessed January 3, 2026)

Aaron’s interpretation of this classic is spot on. He has gotten all the voices just right, from kindly Fred down to Tiny Tim.

Aaron’s interpretation of this classic is spot on. He has gotten all the voices just right, from kindly Fred down to Tiny Tim. “Marley was dead, to begin with. There is no doubt whatever about that. The register of his burial was signed by the clergyman, the clerk, the undertaker, and the chief mourner. Scrooge signed it. And Scrooge’s name was good upon ‘Change for anything he chose to put his hand to. Old Marley was as dead as a doornail.”

“Marley was dead, to begin with. There is no doubt whatever about that. The register of his burial was signed by the clergyman, the clerk, the undertaker, and the chief mourner. Scrooge signed it. And Scrooge’s name was good upon ‘Change for anything he chose to put his hand to. Old Marley was as dead as a doornail.” As I mentioned before, this book is only a novella. It was comprised of 66 handwritten pages. Some people think they aren’t “a real author” if they don’t write a 900-page doorstop, but Dickens proves them wrong.

As I mentioned before, this book is only a novella. It was comprised of 66 handwritten pages. Some people think they aren’t “a real author” if they don’t write a 900-page doorstop, but Dickens proves them wrong.

Title: The Sycamores by Alexandre Calame

Title: The Sycamores by Alexandre Calame