Title: Children’s Games

Title: Children’s Games

Artist: Pieter Bruegel the Elder

Year: 1560

Type: Oil on panel

Dimensions: 118 cm × 161 cm (46 in × 63 in)

Location: Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

What I love about this image:

Pieter Brugel the Elder was one of my first influences in the world of art appreciation. I love the chaos, the raucous jumble of humanity that Brugel always brought to a scene. It is as wild and noisy as his more famous composition, The Wedding Dance. Children have taken over the city and everything is fair game. Brugel’s depiction of village children and their play offered him an opportunity to shine a small light on the hubris and arrogance of mankind, using allegory and misdirection.

About this painting via Wikipedia:

The entire composition is full of children playing a wide variety of games. Over 90 different games that were played by children at the time have been identified.

The artist’s intention for this work is more serious than simply to compile an illustrated encyclopaedia of children’s games, though some eighty particular games have been identified. Bruegel shows the children absorbed in their games with the seriousness displayed by adults in their apparently more important pursuits. His moral is that in the mind of God, children’s games possess as much significance as the activities of their parents. This idea was a familiar one in contemporary literature: in an anonymous Flemish poem published in Antwerp in 1530 by Jan van Doesborch, mankind is compared to children who are entirely absorbed in their foolish games and concerns. [1]

About the Artist, via Wikipedia:

Pieter Bruegel (also Brueghel or Breughel) the Elder c. 1525–1530 – 9 September 1569) was the most significant artist of Dutch and Flemish Renaissance painting, a painter and printmaker from Brabant, known for his landscapes and peasant scenes (so-called genre painting); he was a pioneer in making both types of subject the focus in large paintings.

He was a formative influence on Dutch Golden Age painting and later painting in general in his innovative choices of subject matter, as one of the first generation of artists to grow up when religious subjects had ceased to be the natural subject matter of painting. He also painted no portraits, the other mainstay of Netherlandish art. After his training and travels to Italy, he returned in 1555 to settle in Antwerp, where he worked mainly as a prolific designer of prints for the leading publisher of the day. Only towards the end of the decade did he switch to make painting his main medium, and all his famous paintings come from the following period of little more than a decade before his early death, when he was probably in his early forties, and at the height of his powers.

Around 1563, Bruegel moved from Antwerp to Brussels, where he married Mayken Coecke, the daughter of the painter Pieter Coecke van Aelst and Mayken Verhulst. As registered in the archives of the Cathedral of Antwerp, their deposition for marriage was registered 25 July 1563. The marriage itself was concluded in the Chapel Church, Brussels in 1563.

Pieter the Elder had two sons: Pieter Brueghel the Younger and Jan Brueghel the Elder (both kept their name as Brueghel). Their grandmother, Mayken Verhulst, trained the sons because “the Elder” died when both were very small children. The older brother, Pieter Brueghel copied his father’s style and compositions with competence and considerable commercial success. Jan was much more original, and very versatile. He was an important figure in the transition to the Baroque style in Flemish Baroque painting and Dutch Golden Age painting in a number of its genres. He was often a collaborator with other leading artists, including with Peter Paul Rubens on many works including the Allegory of Sight.

Other members of the family include Jan van Kessel the Elder (grandson of Jan Brueghel the Elder) and Jan van Kessel the Younger. Through David Teniers the Younger, son-in-law of Jan Brueghel the Elder, the family is also related to the whole Teniers family of painters and the Quellinus family of painters and sculptors, through the marriage of Jan-Erasmus Quellinus to Cornelia, daughter of David Teniers the Younger. [2]

Credits and Attributions:

IMAGE: Children’s Games, Wikimedia Commons contributors, “File:Pieter Bruegel the Elder – Children’s Games – Google Art Project.jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Pieter_Bruegel_the_Elder_-_Children%E2%80%99s_Games_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg&oldid=725602746 (accessed April 26, 2024).

[1] Wikipedia contributors, “Children’s Games (Bruegel),” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Children%27s_Games_(Bruegel)&oldid=1198935116 (accessed April 26, 2024).

[2] Wikipedia contributors, “Pieter Bruegel the Elder,” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Pieter_Bruegel_the_Elder&oldid=1218696694 (accessed April 26, 2024).

We rely on water generated by glaciers on Mount Rainier and the Cascade Mountains in general, so the low snowpack means trouble later down the road.

We rely on water generated by glaciers on Mount Rainier and the Cascade Mountains in general, so the low snowpack means trouble later down the road.

I grew up in an isolated rural environment, and summers could be lonely. My sister and I would get away from family dynamics by reading. My favorite “We Don’t Have Anything to Read” book was the volume of collected works by William Butler Yeats. That book shaped my view of poetry and literature in general.

I grew up in an isolated rural environment, and summers could be lonely. My sister and I would get away from family dynamics by reading. My favorite “We Don’t Have Anything to Read” book was the volume of collected works by William Butler Yeats. That book shaped my view of poetry and literature in general. Sometimes, poetry is long, even epic in length. The epic poem,

Sometimes, poetry is long, even epic in length. The epic poem,  Poets select words for the impact they deliver. An entire story must be conveyed using the least number of words possible. Choices are made for symbolism, power, and syllabic cadence, even if there is no rhyme involved.

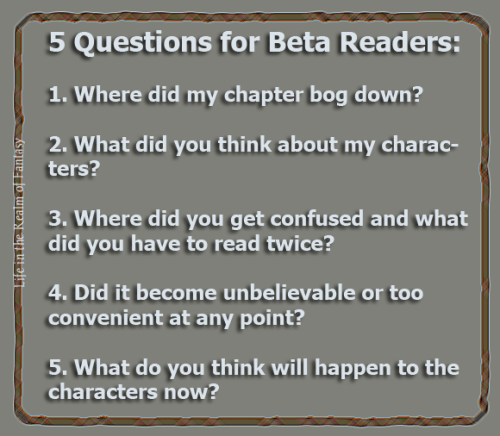

Poets select words for the impact they deliver. An entire story must be conveyed using the least number of words possible. Choices are made for symbolism, power, and syllabic cadence, even if there is no rhyme involved. When prepping a novel to send to Irene, I use a three-part method. This requires specific tools that come with Microsoft Word, my word-processing program. I believe these tools are available for Google Docs and every other word-processing program. Unfortunately, I am only familiar with Microsoft’s products as they are what the companies that I worked for used.

When prepping a novel to send to Irene, I use a three-part method. This requires specific tools that come with Microsoft Word, my word-processing program. I believe these tools are available for Google Docs and every other word-processing program. Unfortunately, I am only familiar with Microsoft’s products as they are what the companies that I worked for used. Part two: Once I have ironed out the rough spots noticed by my beta readers, this second stage is put into action. Yes, on the surface the manuscript looks finished, but it has only just begun the journey.

Part two: Once I have ironed out the rough spots noticed by my beta readers, this second stage is put into action. Yes, on the surface the manuscript looks finished, but it has only just begun the journey. The most frustrating part is the continual stopping, making corrections, and starting.

The most frustrating part is the continual stopping, making corrections, and starting.

I am wary of relying on

I am wary of relying on  If you read as much as I do (and this includes books published by large Traditional publishers), you know that a few mistakes and typos can and will get through despite their careful editing. So, don’t agonize over what you might have missed. If you’re an indie, you can upload a corrected file.

If you read as much as I do (and this includes books published by large Traditional publishers), you know that a few mistakes and typos can and will get through despite their careful editing. So, don’t agonize over what you might have missed. If you’re an indie, you can upload a corrected file.

Last week, we talked about how punctuation is the traffic signal that keeps our words flowing smoothly.

Last week, we talked about how punctuation is the traffic signal that keeps our words flowing smoothly. If the meaning is understood when two words are combined into one, and common usage writes it as one word, again a hyphen is unnecessary.

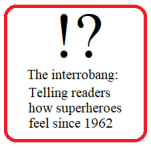

If the meaning is understood when two words are combined into one, and common usage writes it as one word, again a hyphen is unnecessary. But what about !? These mutant morsels of madness are called “interrobangs.”

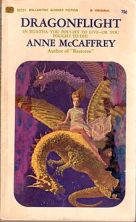

But what about !? These mutant morsels of madness are called “interrobangs.” One of my favorite authors, Ann McCaffrey, set off telepathic conversations with both italics and colons in the place of quote marks.

One of my favorite authors, Ann McCaffrey, set off telepathic conversations with both italics and colons in the place of quote marks. I certainly didn’t. If these authors hope to find an agent or successfully self-publish, they have a lot of work and self-education ahead of them.

I certainly didn’t. If these authors hope to find an agent or successfully self-publish, they have a lot of work and self-education ahead of them. If you are writing in the US, you might consider investing in

If you are writing in the US, you might consider investing in  Let’s get two newbie mistakes out of the way:

Let’s get two newbie mistakes out of the way:

All three of the above sentences are technically correct. The usage you habitually choose is your voice.

All three of the above sentences are technically correct. The usage you habitually choose is your voice. Why are these rules so important? Punctuation tames the chaos that our prose can become. Periods, commas, quotation marks–these are the universally acknowledged traffic signals.

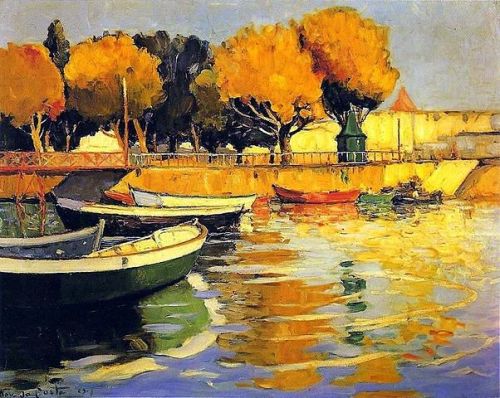

Why are these rules so important? Punctuation tames the chaos that our prose can become. Periods, commas, quotation marks–these are the universally acknowledged traffic signals. Artist: Mário Navarro da Costa (1883-1931)

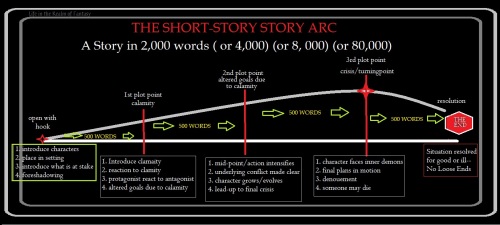

Artist: Mário Navarro da Costa (1883-1931) So now, we realize that we must submit our work to contests or publications if we ever want to get our name out there. We have looked at our backlog of short stories and gone out to sites like

So now, we realize that we must submit our work to contests or publications if we ever want to get our name out there. We have looked at our backlog of short stories and gone out to sites like  The first thing we’re going to look at is the problem. Is the problem worth having a story written around it? If not, is this a “people in a situation” story, such as a short romance or a scene in a counselor’s office? What is the problem and why did the characters get involved in it?

The first thing we’re going to look at is the problem. Is the problem worth having a story written around it? If not, is this a “people in a situation” story, such as a short romance or a scene in a counselor’s office? What is the problem and why did the characters get involved in it? Worldbuilding is crucial in a short story. Is the setting I have chosen the right place for this event to happen? In this case, I say yes, that it is the only place where such a story could happen.

Worldbuilding is crucial in a short story. Is the setting I have chosen the right place for this event to happen? In this case, I say yes, that it is the only place where such a story could happen. Point of view: First person – Oriana tells us this story as it happens. We are in her head for the entire story. Do her actions and reactions feel organic and natural? After some work, I think yes, but again, I’ll have to run it by someone to be sure.

Point of view: First person – Oriana tells us this story as it happens. We are in her head for the entire story. Do her actions and reactions feel organic and natural? After some work, I think yes, but again, I’ll have to run it by someone to be sure.

I am not the only person who experiences these moments of low creative energy. When this happens, I set the longer work aside and go rogue—I write poetry and drabbles and short stories.

I am not the only person who experiences these moments of low creative energy. When this happens, I set the longer work aside and go rogue—I write poetry and drabbles and short stories. Maybe you are writing, but so far, you have written nothing novel or even novella-length. Perhaps you have been writing a little of this and a bit of that, and now you have a pile of disparate, exceptionally short fiction, and you don’t know what to do with it.

Maybe you are writing, but so far, you have written nothing novel or even novella-length. Perhaps you have been writing a little of this and a bit of that, and now you have a pile of disparate, exceptionally short fiction, and you don’t know what to do with it. Microfiction is the distilled soul of a novel. It has everything the reader needs to know about a singular moment in time. It tells that story and makes the reader wonder what happened next. Each short piece we write increases our ability to tell a story with minimal exposition.

Microfiction is the distilled soul of a novel. It has everything the reader needs to know about a singular moment in time. It tells that story and makes the reader wonder what happened next. Each short piece we write increases our ability to tell a story with minimal exposition. When submitting to a publication, you send your work directly to the publisher. In return, you can expect to receive a communication from the senior editor, either a rejection or an acceptance.

When submitting to a publication, you send your work directly to the publisher. In return, you can expect to receive a communication from the senior editor, either a rejection or an acceptance. To wind this up—take another look at that backlog of short work. Edit it, read it aloud, and edit it again. Then, consider submitting that work to a contest or magazine. It’s good experience for indie writers, but more than that, you might hit the jackpot!

To wind this up—take another look at that backlog of short work. Edit it, read it aloud, and edit it again. Then, consider submitting that work to a contest or magazine. It’s good experience for indie writers, but more than that, you might hit the jackpot! Artist: Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890)

Artist: Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890)